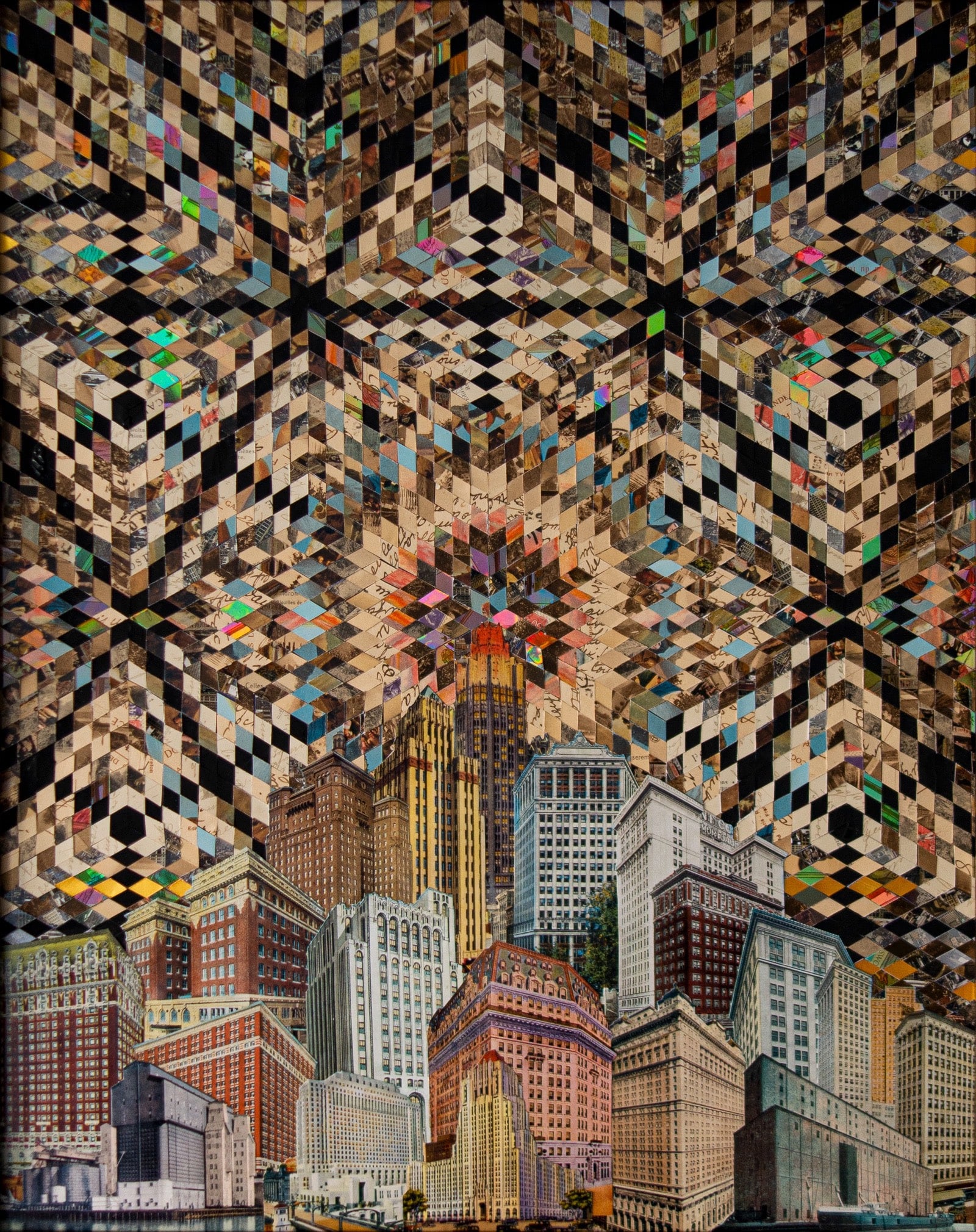

At the beginning of a 1930 radio broadcast for kids, Walter Benjamin called upon his audience to search their memories. ‘I bet that if you try,’ he said, ‘you can remember seeing wardrobes or armoires with colorful scenes, landscapes, portraits, flowers, fruits, or other similar designs inlaid in the wood of their doors. Intarsia is what it’s called.’

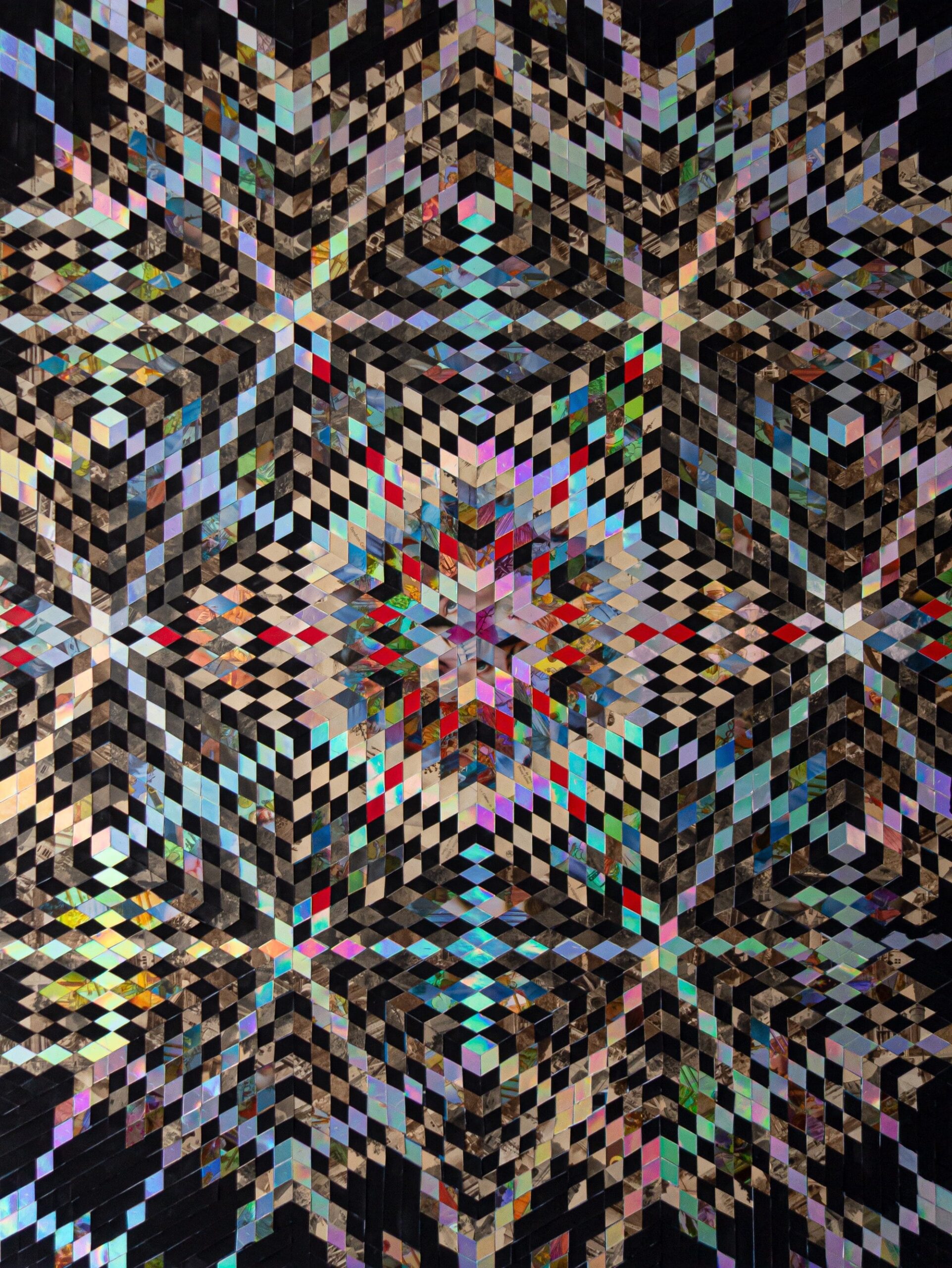

Benjamin was invoking a sort of mosaic method that gives the impression of depth through the superposing of wood. These days intarsia also refers to a similar technique of illusory layering in knitting. For Benjamin, intarsia was a great metaphor, a model for his program to follow, a giddying montage piece covering a variety of Berlin childhoods throughout the ages—‘scenes inlaid not in wood, but in speech.’

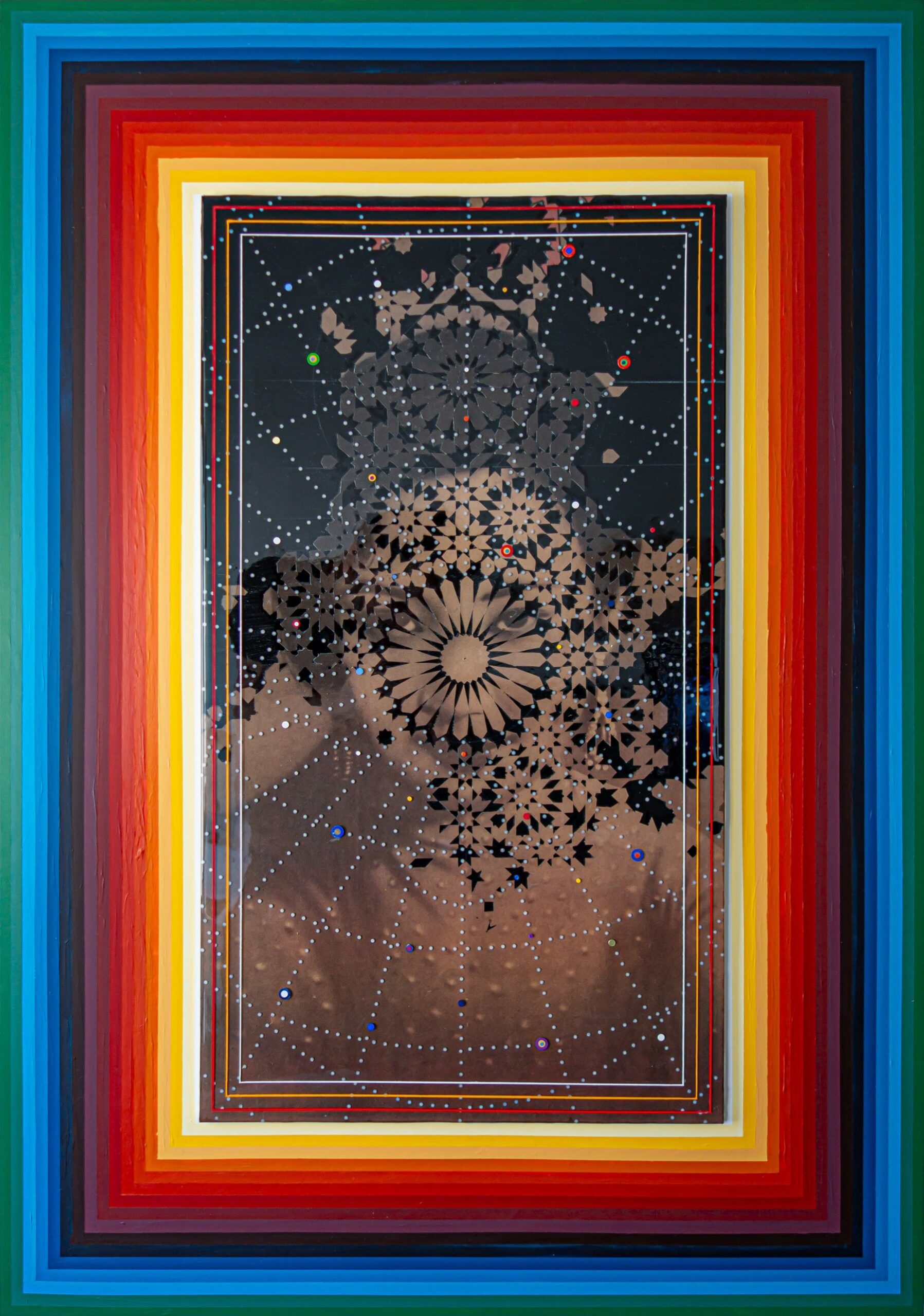

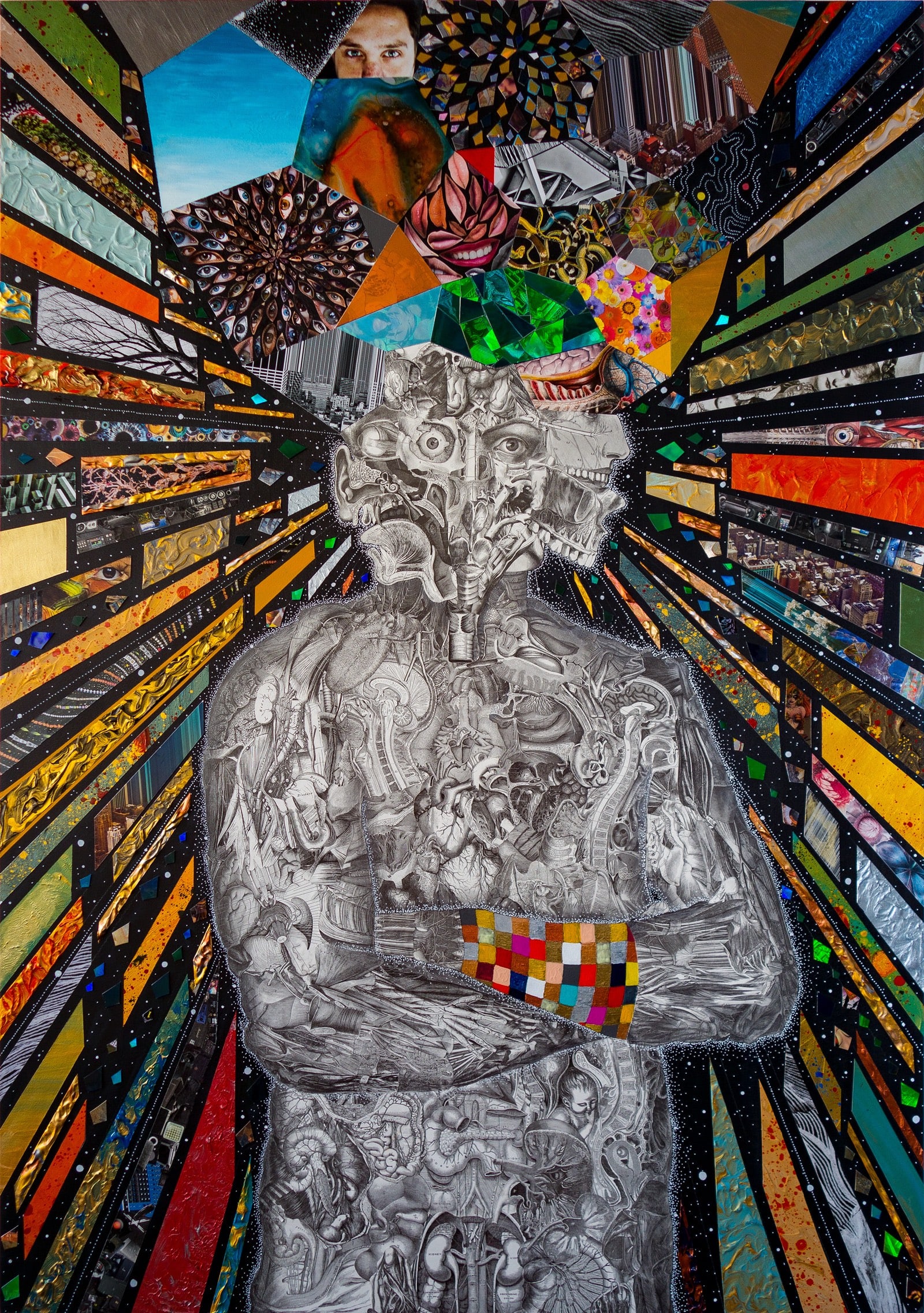

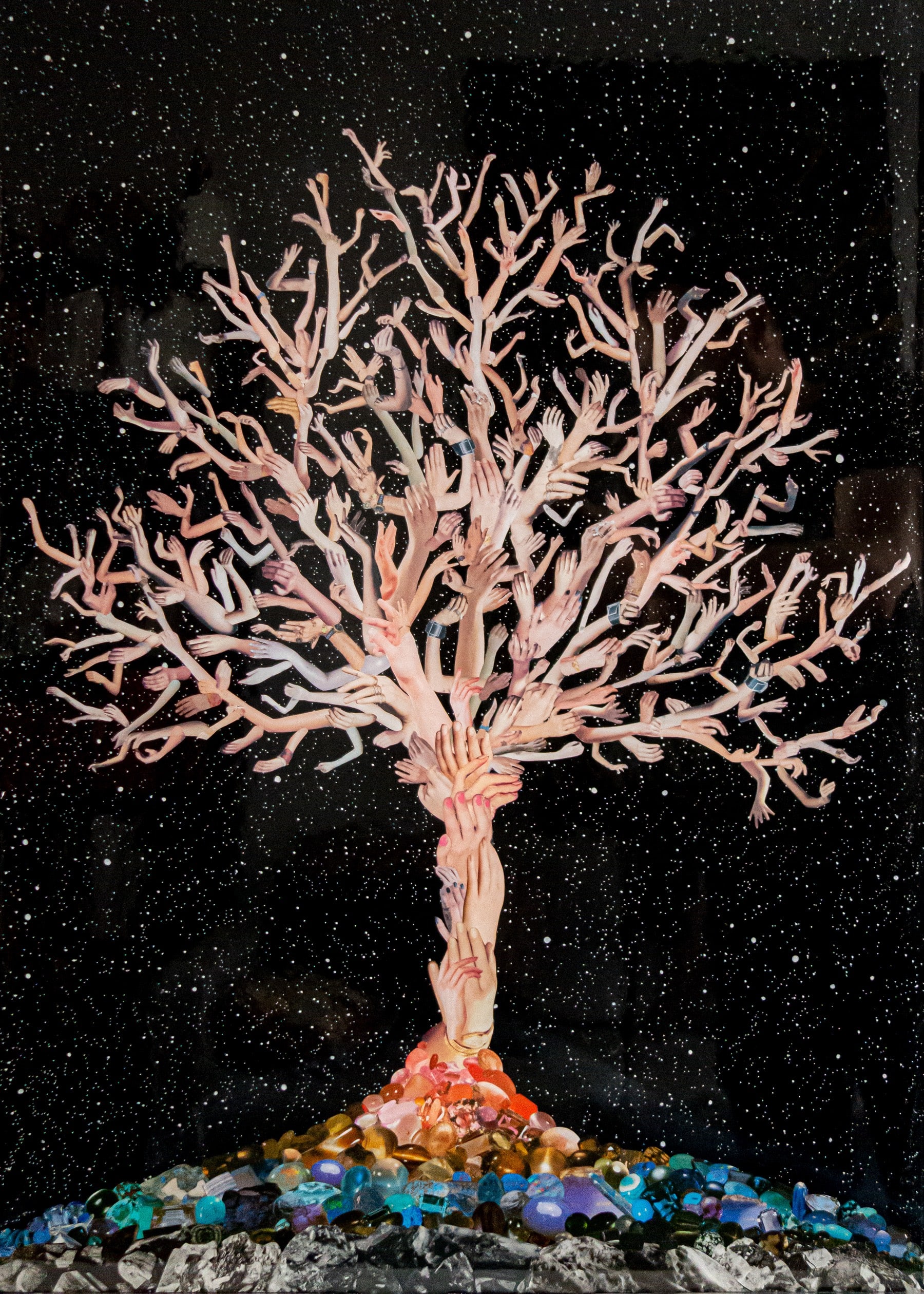

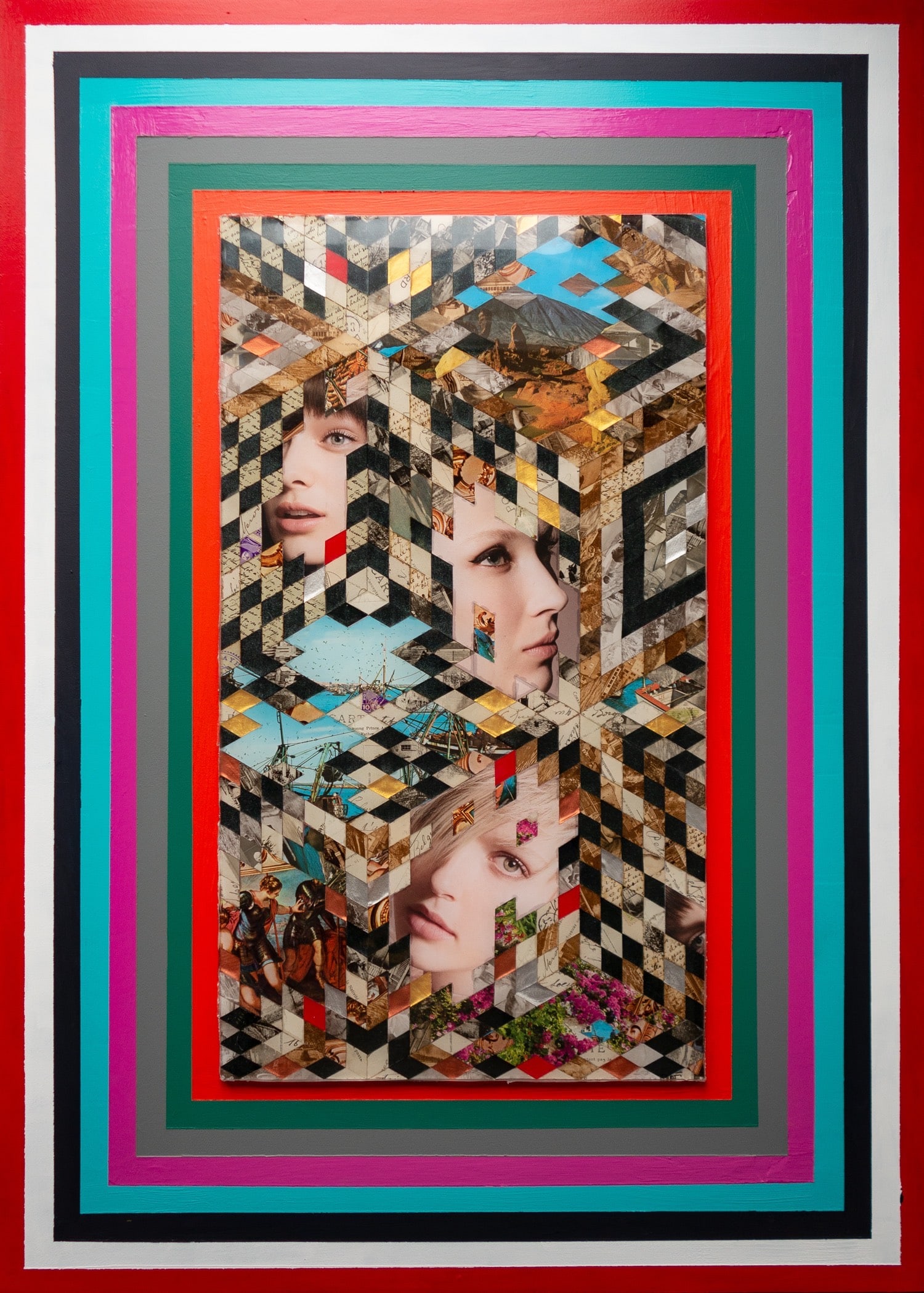

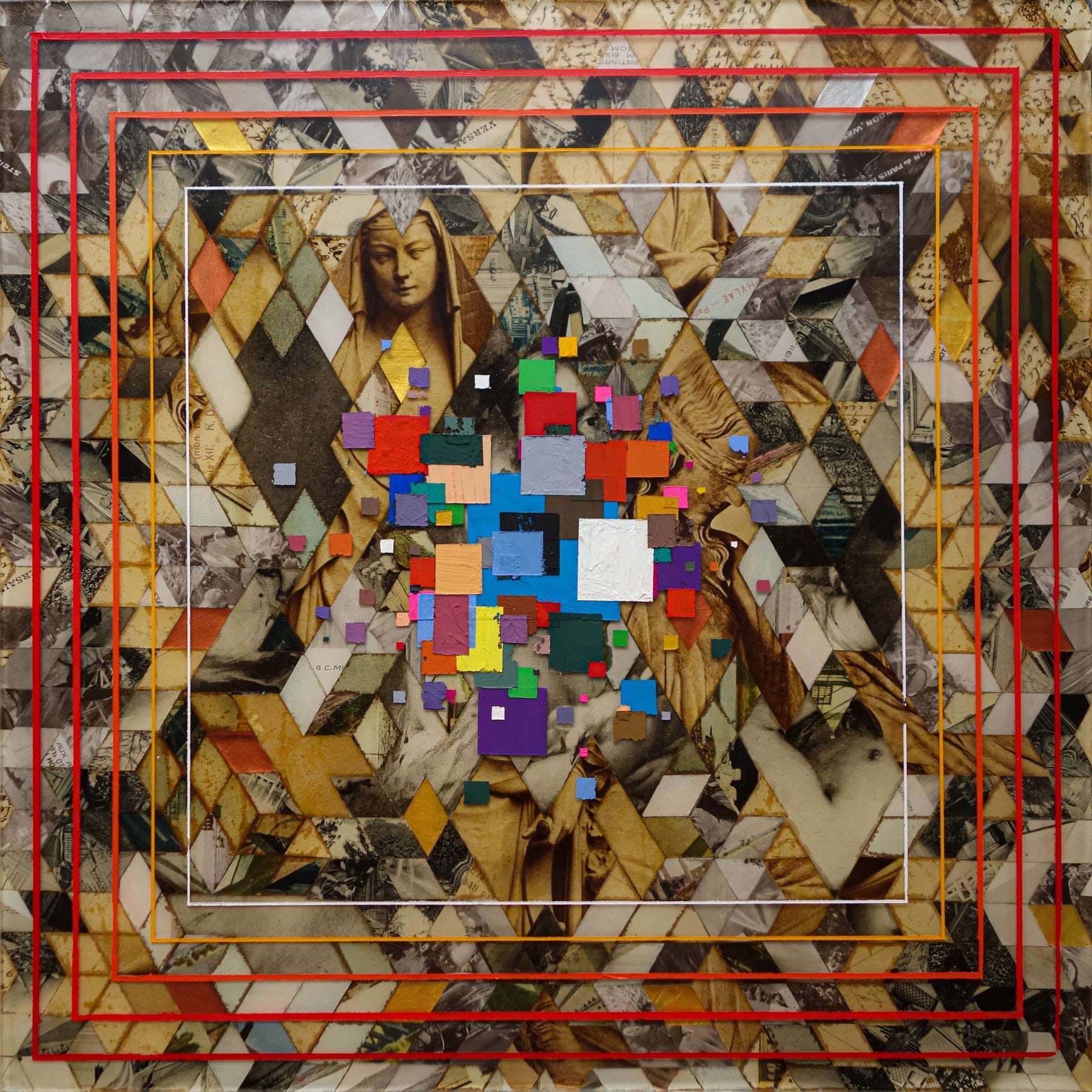

Intarsia happens to be the name of David Crunelle’s first collection of new collages in over two years. It’s one hell of a trip. If Benjamin employed intarsia metaphorically, weaving stories to startling effect, so, too, does Crunelle, who likewise engages in an obsessive layering of all sorts of ‘stories’: postcards from the 1920s through the 1960s; decade-old pictures of new york; communist propaganda posters from china; and surprisingly, photographs from the artist’s own childhood. These collages glisten like radiant jewels.

Yet what of all this talk of intarsia as a ruse in which depth is but a trick of the light? Surely we aren’t saying that this a shallow form of art—and that Benjamin and Crunelle, in pursuing intarsia in their own weird ways, are pulling a fast one?

The apparently contradictory answer is that intarsia demands considerable skill, its spectacular illusion the result of an especially intricate, labor-intensive craft—like professional wrestling, say, in which real blood is spilled and real backs have broken in the name of performance. It is not that surface appearance is a ‘lie’, but rather that surface and whatever lies ‘below’ speak one to the other incessantly, the former concealing yet wholly defined by the latter.

This tension was at the heart of what Marx called commodity fetishism. Capitalist society, he wrote, ‘appears’ as a mass of commodities, eliding the human labor that has gone into them. Social relations thus take the form of relations between things, magical things floating about the marketplace all on their own.

Crunelle’s great skill is in what we might call riding the fetish—comingling surface and depth such that you can’t tell which is which. It is quite an achievement.