On 17 January 1938, shortly before a planned visit to New York City, the artist and Soviet propagandist Gustav Klutsis was arrested in Moscow and, six weeks later, killed on Stalin’s order. Some thanks, you want to say. After all, Klutsis, in collaboration with his wife, Valentina Kulagina, made on-command eye candy out of some of the regime’s dreariest and most long-winded slogans, like ‘Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country’. The obvious and easy questions to ask here are those which raise the inevitability of Klutsis’s death: ‘Do politics and art mix?’, whatever mixing might mean, or ‘Is an artist working for the government already dead?’

We’ve got it all wrong. Obvious and easy questions aren’t going to get us anywhere. ‘How can politics and art not mix?’ is better, but still, this sets up two camps: politics, over there, far away, and resolutely not an artform; and art, something more proletarian, perhaps, and resolutely not a legitimate form of political discourse. It’s one or the other. And still we’re no closer to solving this whole mixing conundrum.

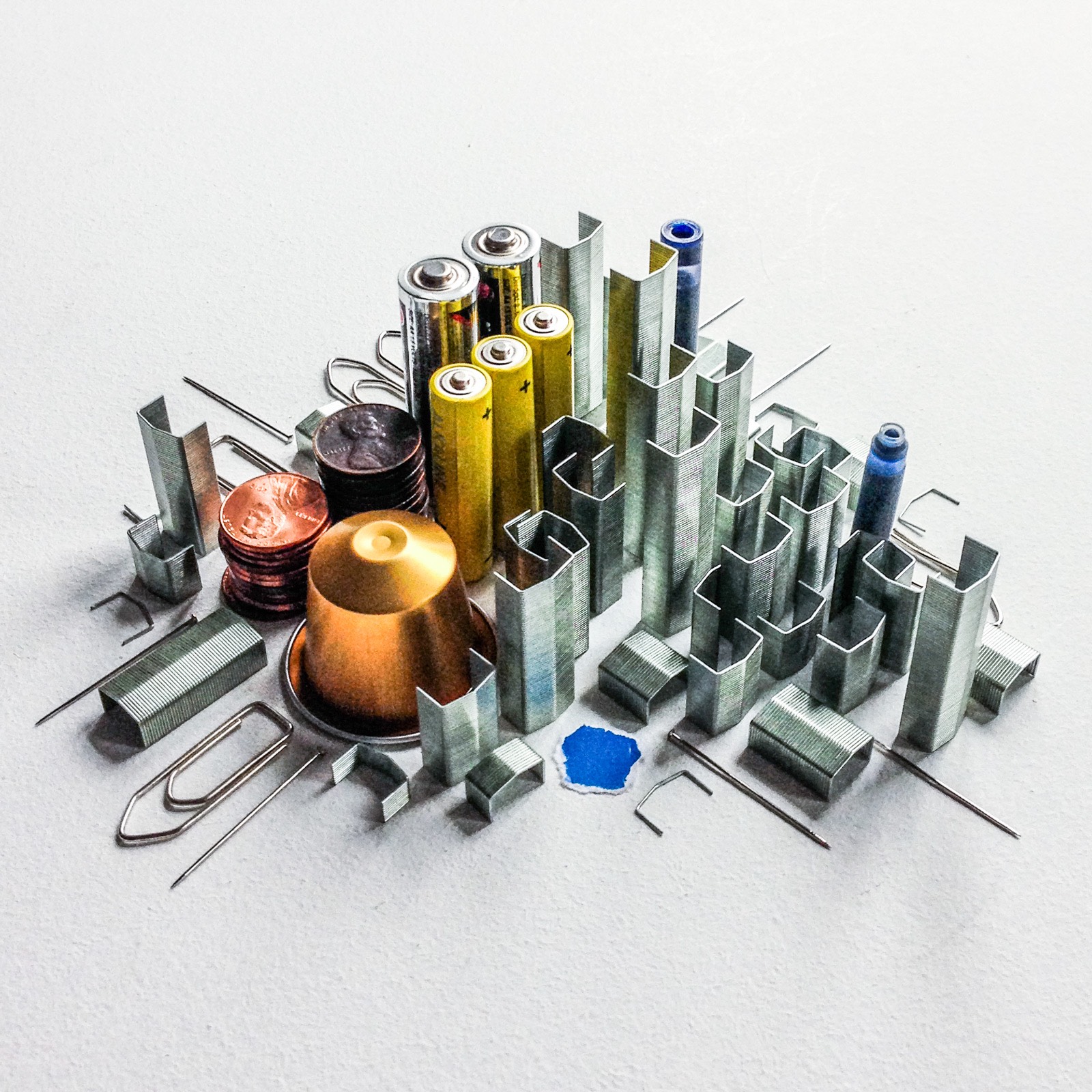

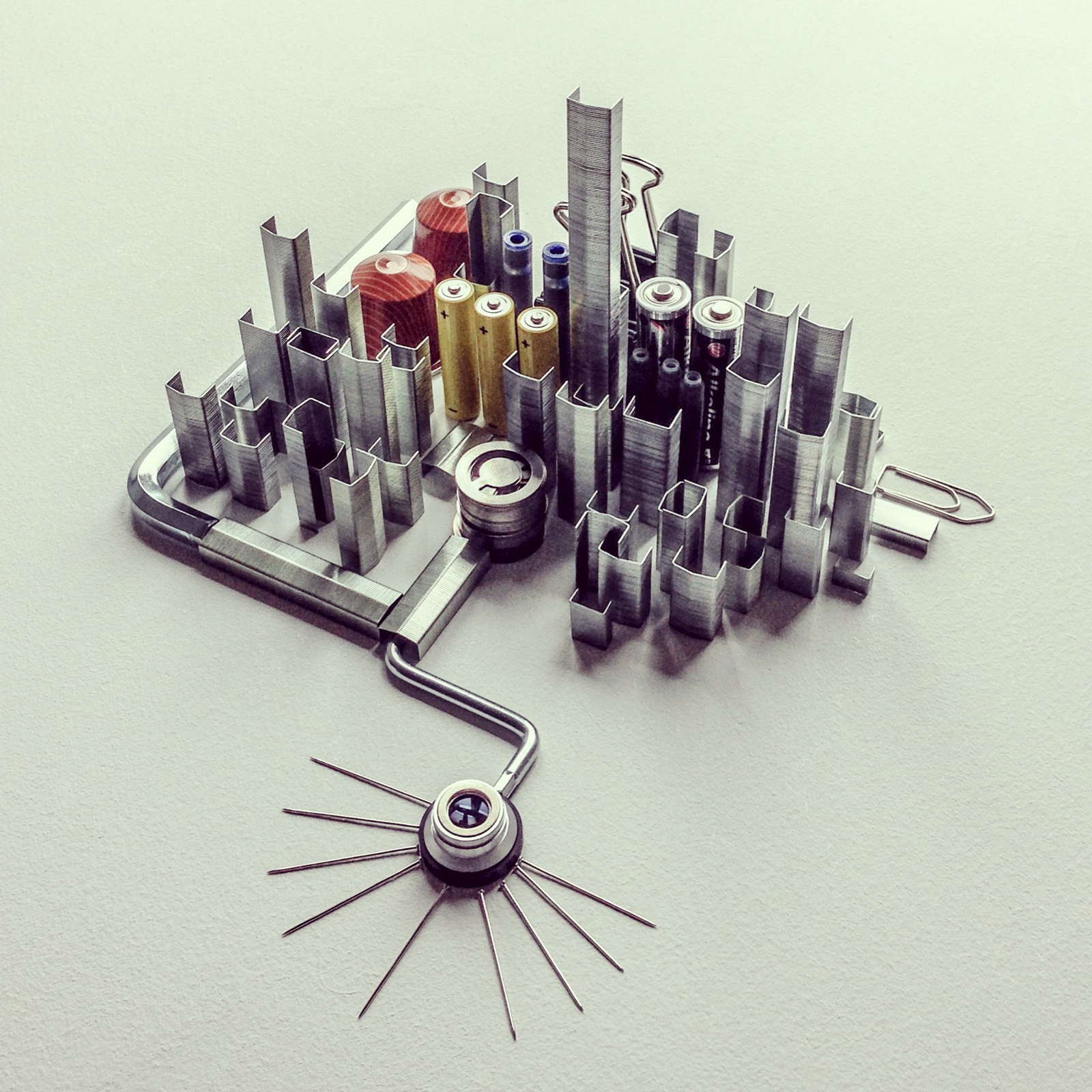

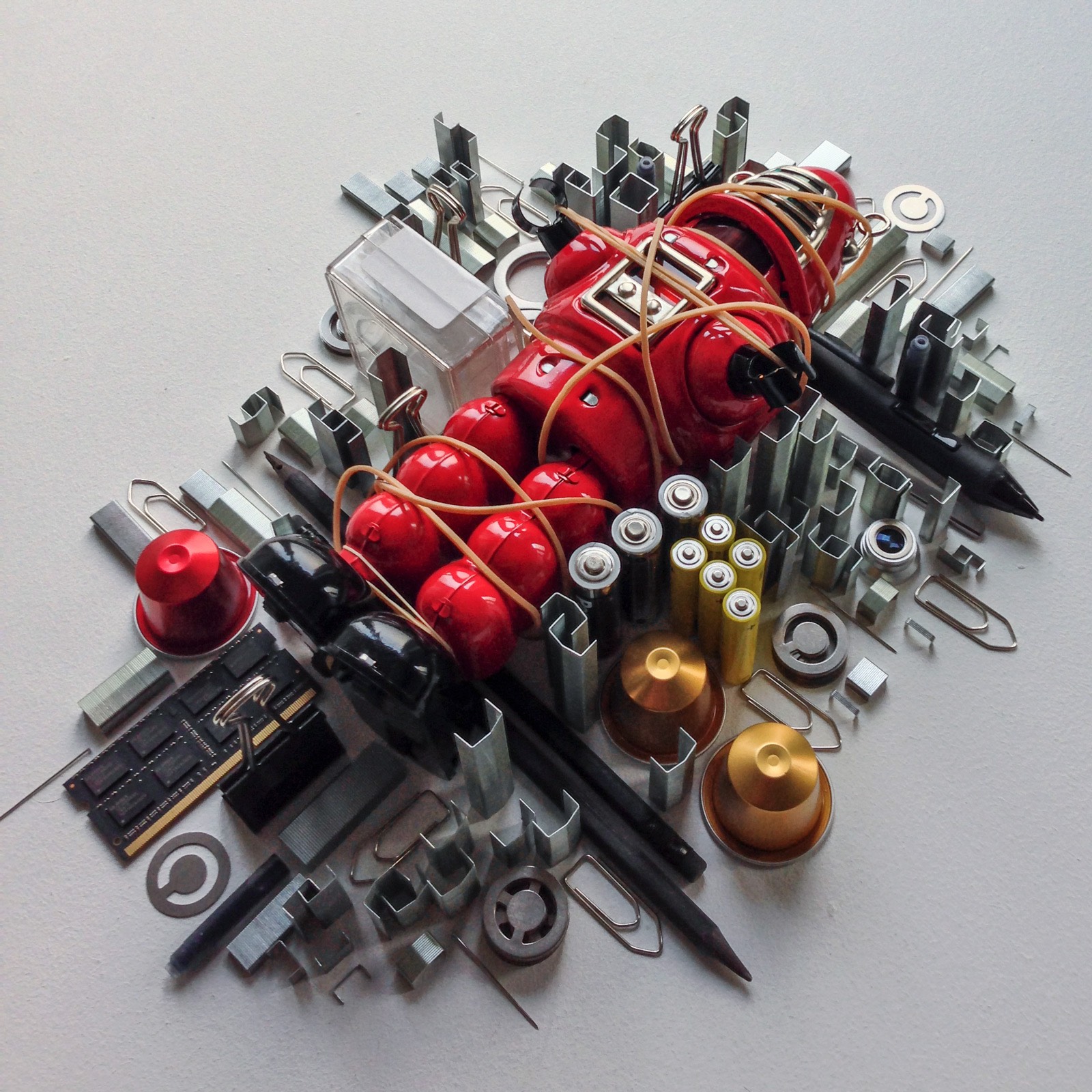

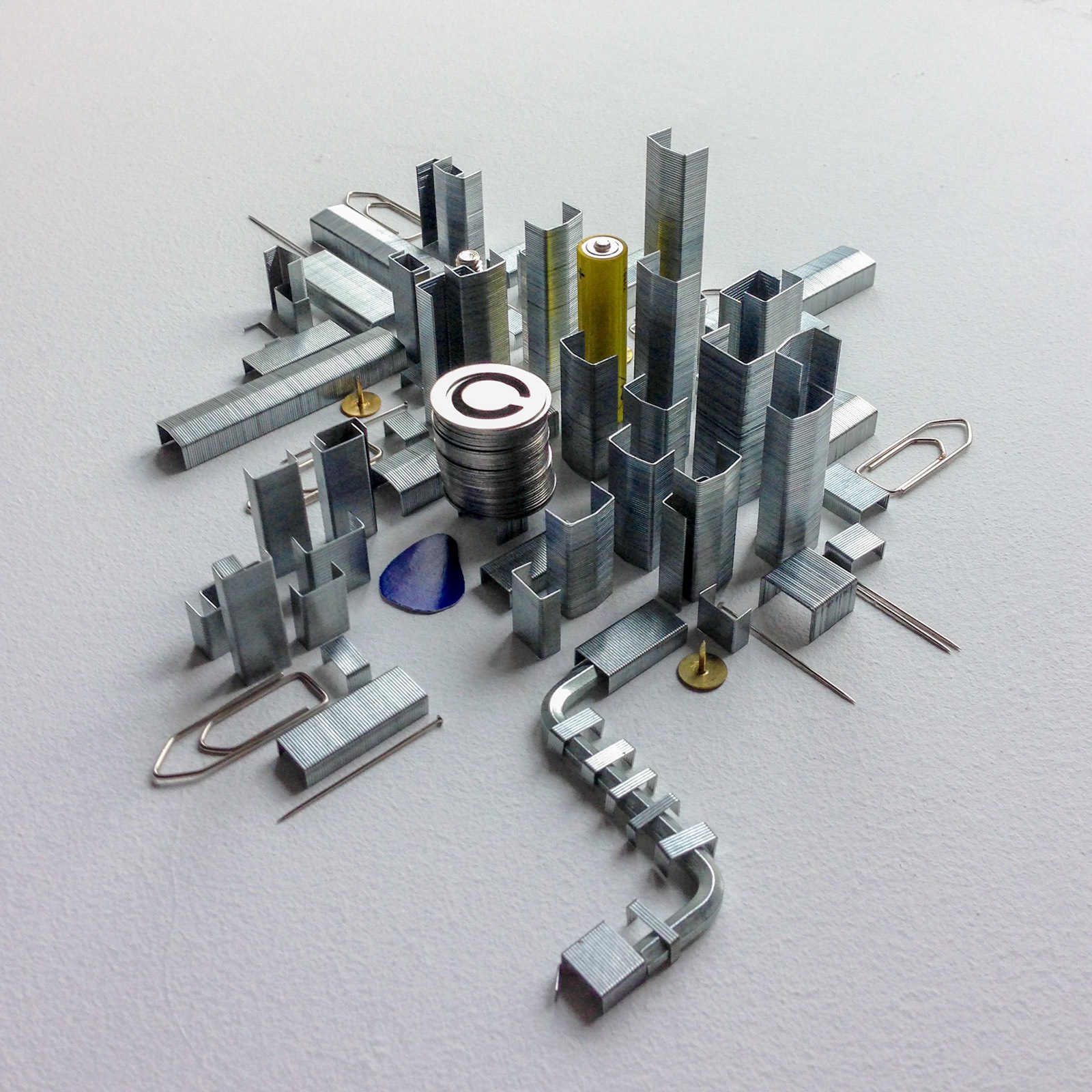

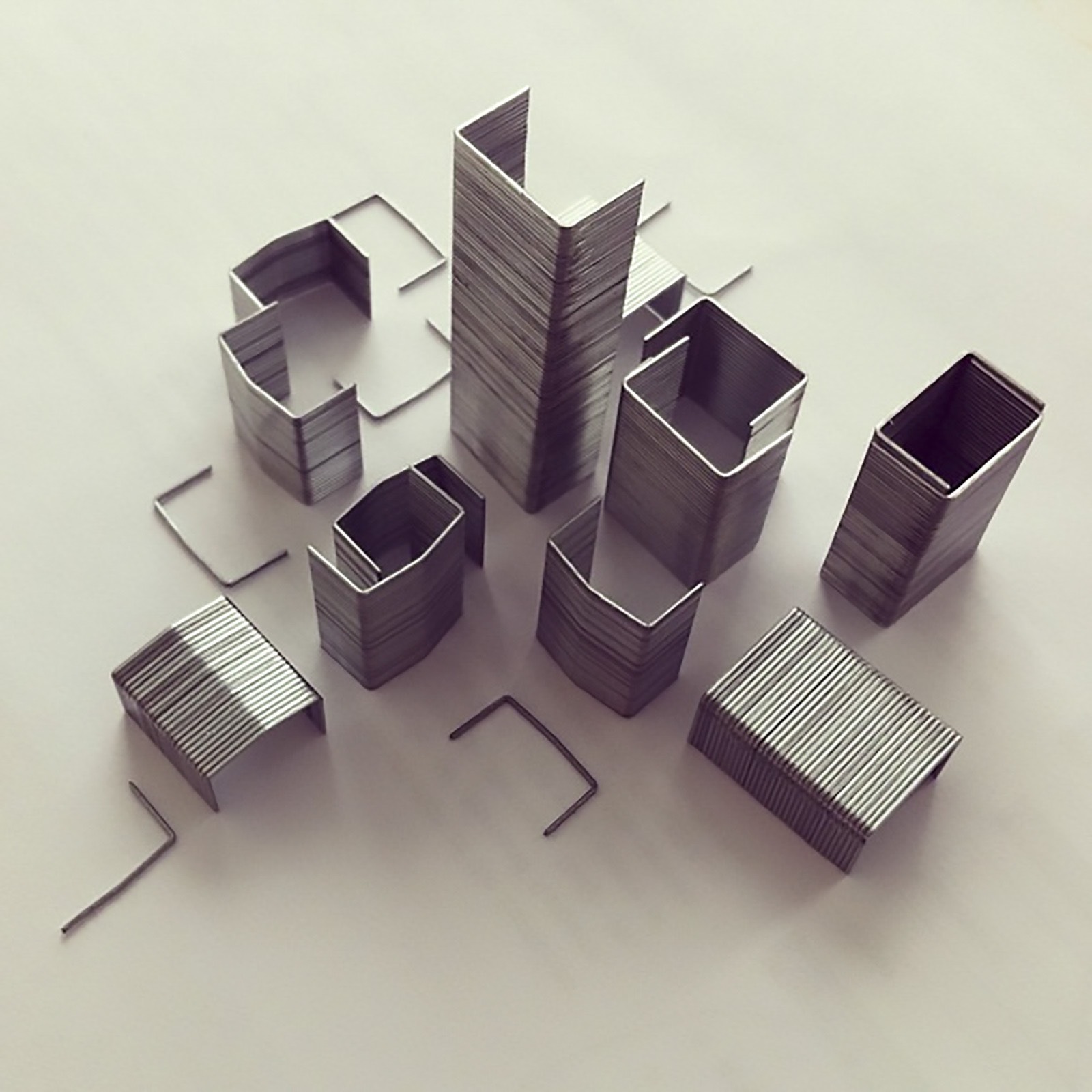

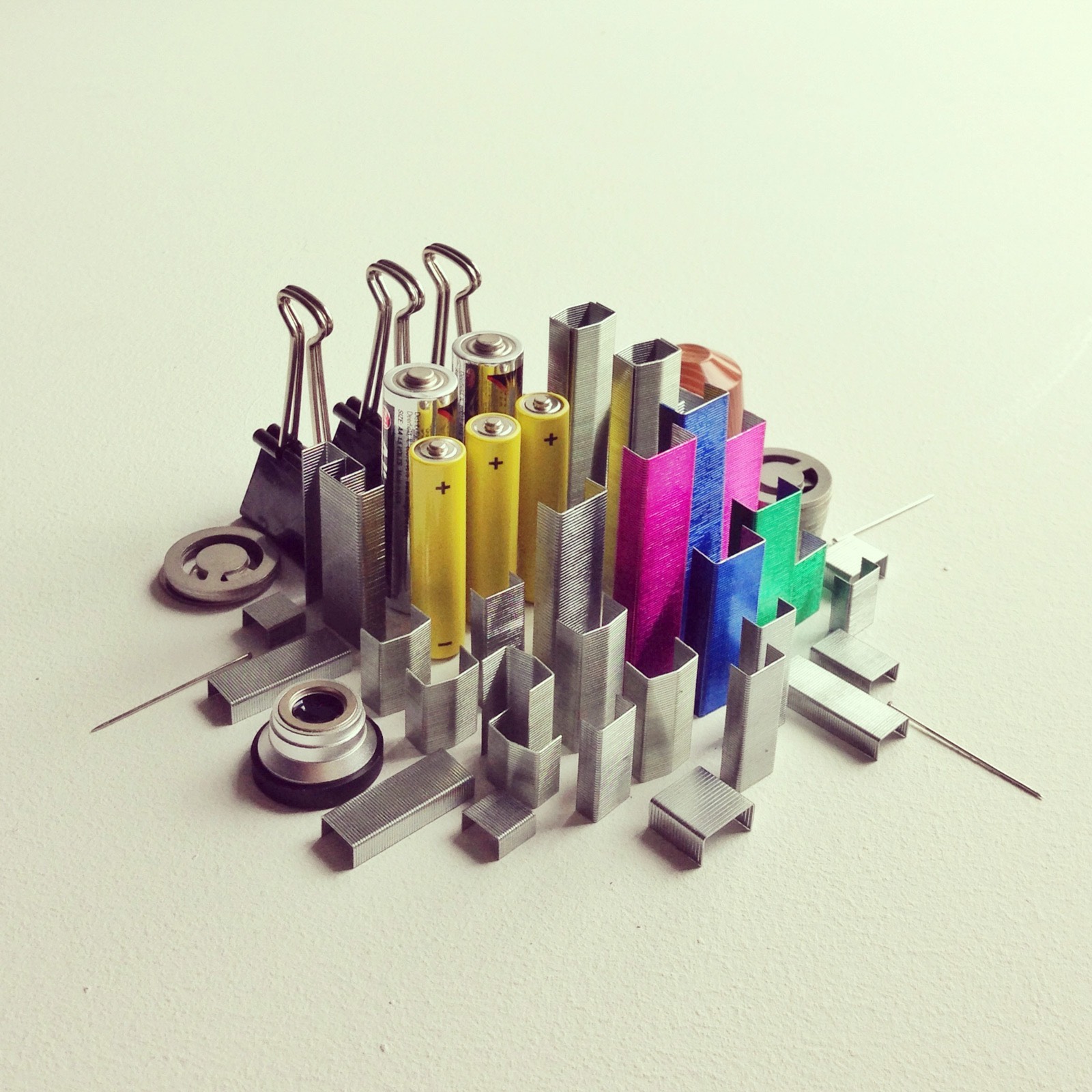

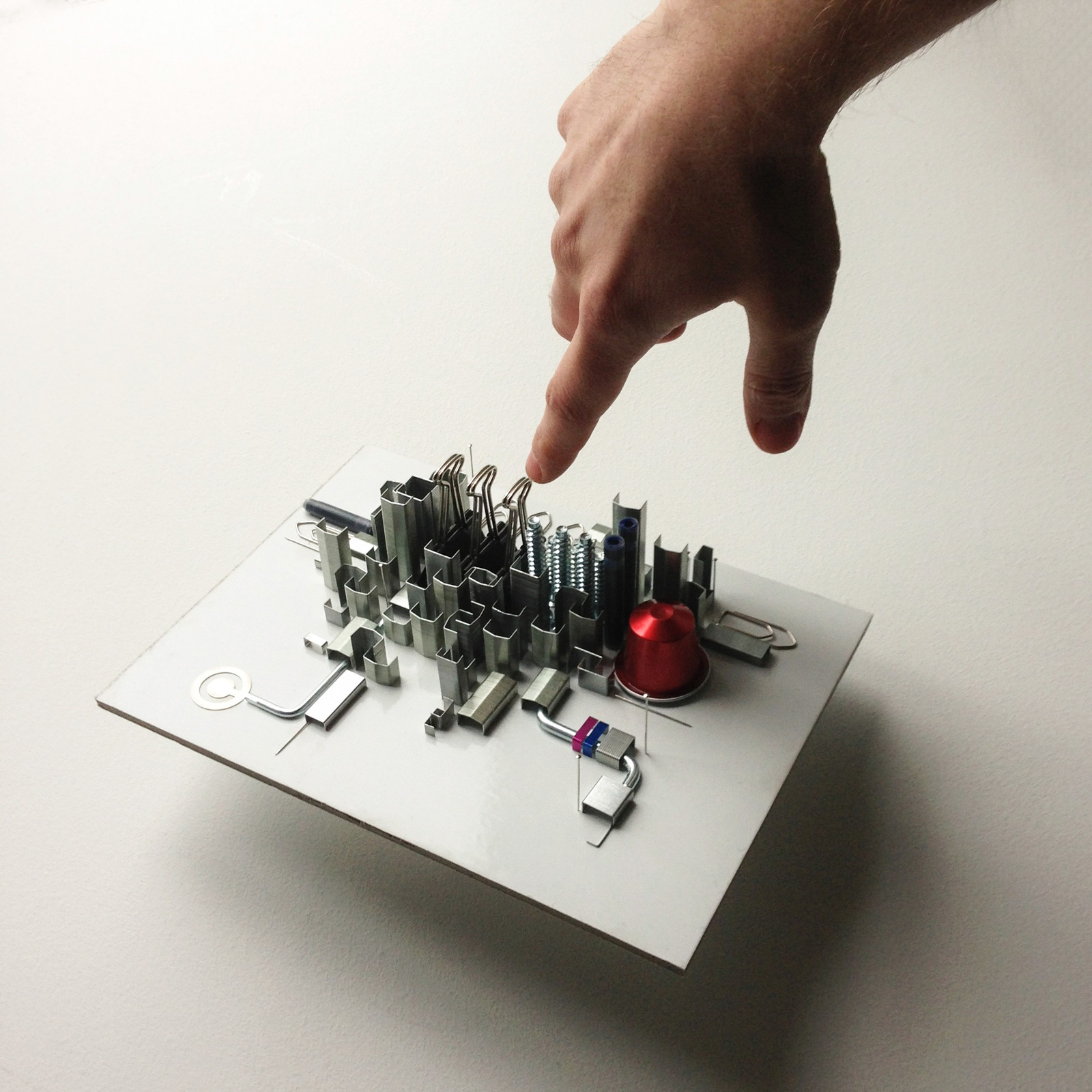

The Stapletown Project, however, busts wide open the above so-called disconnect. Immerse yourself totally in these stationery cityscapes, and, before long, your aesthetic sensibilities get recircuited. The potential artistic energy of the workaday screams out wherever you look, and the words of Klaus von Beyme come hurtling to the fore: ‘The knowledge that everything is politics leads us astray if it is not supplemented with the insight that everything is also economics or culture.’

Here’s the rub. Surely the office aesthetic is one of the deftest, most genius acts of artistic sleight of hand around, precisely because it hides so well its very status as art. Its designedness. For what artist, as we understand the word, would be behind the sort of monochrome, life-sapping hell that is the office space, where the most daring things permitted are pot plants and signs noting that you don’t have to be mad to work here, but it helps? So male. So boring, too, and that’s where the genius really lies. What is fundamental is that this aesthetic is unmistakably that of Politics, big P, too, which is similarly all grey suits and grey men. I don’t do politics, one commonly hears. It’s dull.

The Constructivist paradise contained within these pages offers a way out of this bind. So politics has out-arted art. So art must out-art it back. Politicising the staple seems like the only honest place to start.

Installation, photography.